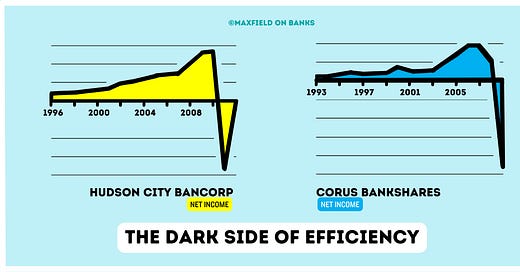

THE DARK SIDE OF EFFICIENCY

Efficiency may be one of the most celebrated ratios in banking — but it can still be taken too far.

“To be a truly conservative investment a company must be the lowest-cost producer or about as low a cost producer as any competitor. It must also give promise of continuing to be so in the future."

Philip Fisher

Conservative Investors Sleep Well (1975)

Ronald E. Hermance Jr. had been eyeing the northern-most suburbs of New York City for months when investment bankers showed up in 2005 to gauge Hudson City Bancorp’s interest in acquiring Sound Federal Credit Union, a $1.2 billion bank based in While Plains, NY.

Hudson City was among the last of a dying breed. Founded in 1868, it had survived three great depressions, a half dozen minor banking panics and the menagerie of crises in the 1980s that had hollowed out much of the mutual savings bank industry. Along the way, most mutual savings banks jettisoned the traditional model by either diversifying into commercial real estate lending or securitizing residential mortgage loans, lubricated by a growing array of checking accounts, savings accounts and brokered deposits. But not Hudson City. It persevered as a monoline thrift. No securitization. No subprime mortgages. Just certificates of deposit financing jumbo mortgages.

Its model was rooted in frugality. “We do two things well: block and tackle,” Hermance once explained. “We underwrite every loan and our operating efficiency is very low." Hudson City eschewed advertising, kept its branches basic, and planted its headquarters in Paramus, New Jersey, a non-imperial corporate redoubt seventeen miles west of the George Washington Bridge connecting Fort Lee, New Jersey, to New York City.

Hudson City boasted one of the lowest, if not the lowest, efficiency ratios in the banking industry. It spent just 21 percent of its net revenue in 2005 on expenses to operate the bank. The typical bank spent nearly three times as much. Hudson City then parlayed these savings into a pricing advantage on both sides of the balance sheet.

“They're lean and mean when it comes to expenses and they compete aggressively on price,” a banking analyst at the time told The Journal News. It might not have offered the absolute lowest rates on mortgages or the absolute highest rates on deposits, but Hudson City could comfortably accommodate both types of customers and still earn a healthy return for its investors.

Hudson City’s earnings more than doubled between 2001 and 2005. Its stock returned 341 percent compared to just 14 percent for the Russell 1000 Index over the same stretch. And in 2002, it generated the highest total return among all publicly traded banks in the United States.

Accolades poured into the bank. Jim Cramer dubbed Hermance a modern-day George Bailey. Slate magazine anointed him America’s Smartest Banker. Forbes magazine named Hudson City the best managed bank of 2007. And it appeared on Businessweek's Top 1000 Global Companies, Forbes’ Elite 500 and Crain’s New York’s annual list of the fastest growing companies.

But now came the hard part. Could Hudson City break the curse that transforms the darlings of one era in banking into the pariahs of the next? It’s in the answer to this question that one discovers a fundamental truth about banking — a truth that would have served the leaders at Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic well. For one learns how easily a potent competitive advantage can become an albatross that hangs around one’s neck.

The gospel of banking

Efficiency is the gospel of banking. In such an industry, Warren Buffett wrote in his 1987 shareholder letter, “only a very low-cost operator or someone operating in a protected, and usually small, niche can sustain high profitability levels.”

Time has proved this out. Yet, time has also proved that gospel can be dangerous if taken too far. In this case, the issue with cutting costs to the bone, so to speak, is that sometimes the bone is sacrificed in the process. U.S. Bancorp arrived at that point in 2006, just as Richard Davis became CEO. Over the next five years, he would execute the greatest turnaround in banking that no one has ever heard of.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Maxfield on Banks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.