Where are we and how did we get here?

Banking in the new world order.

“Business conditions and methods may change with the times but sound banking practice cannot depart from its fundamentals: careful judgment, conservatism and steadiness.”

Toy National Bank

Advertising slogan, 1940

It comes to pass every few years that the markets descend into turmoil. These periods tend to coincide with events that create a dense fog of uncertainty.

Five years ago, nobody knew what a pandemic would do to the economy, so they panicked. We’re seeing the same thing in the markets right now.

The present uncertainty stems from the tariffs announced by President Trump on Wednesday. Liberation day. It was “probably the biggest change” in the economic environment “in my career,” said Howard Marks, the ordinarily reticent co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management. The S&P 500 dropped 10 percent over the next two trading days, with many bank stocks off by that much or more.

The issues we face are complex. They involve exchange rates. Balance of payments. Monetary policy. Consumer and government debt. Indeed, every entry in the dictionary of finance is liable to be touched in some way by the new economic order represented by these tariffs.

Allow me to assuage some uncertainty by laying out the issues at play — what they are, and how we got here. Nobody can predict the future. But if you understand what’s happening right now, you’ll have a better chance of handicapping the most likely future outcomes.

“Trade deficits are no longer merely an economic problem. They are a national emergency.”

President Donald J. Trump

April 2, 2025

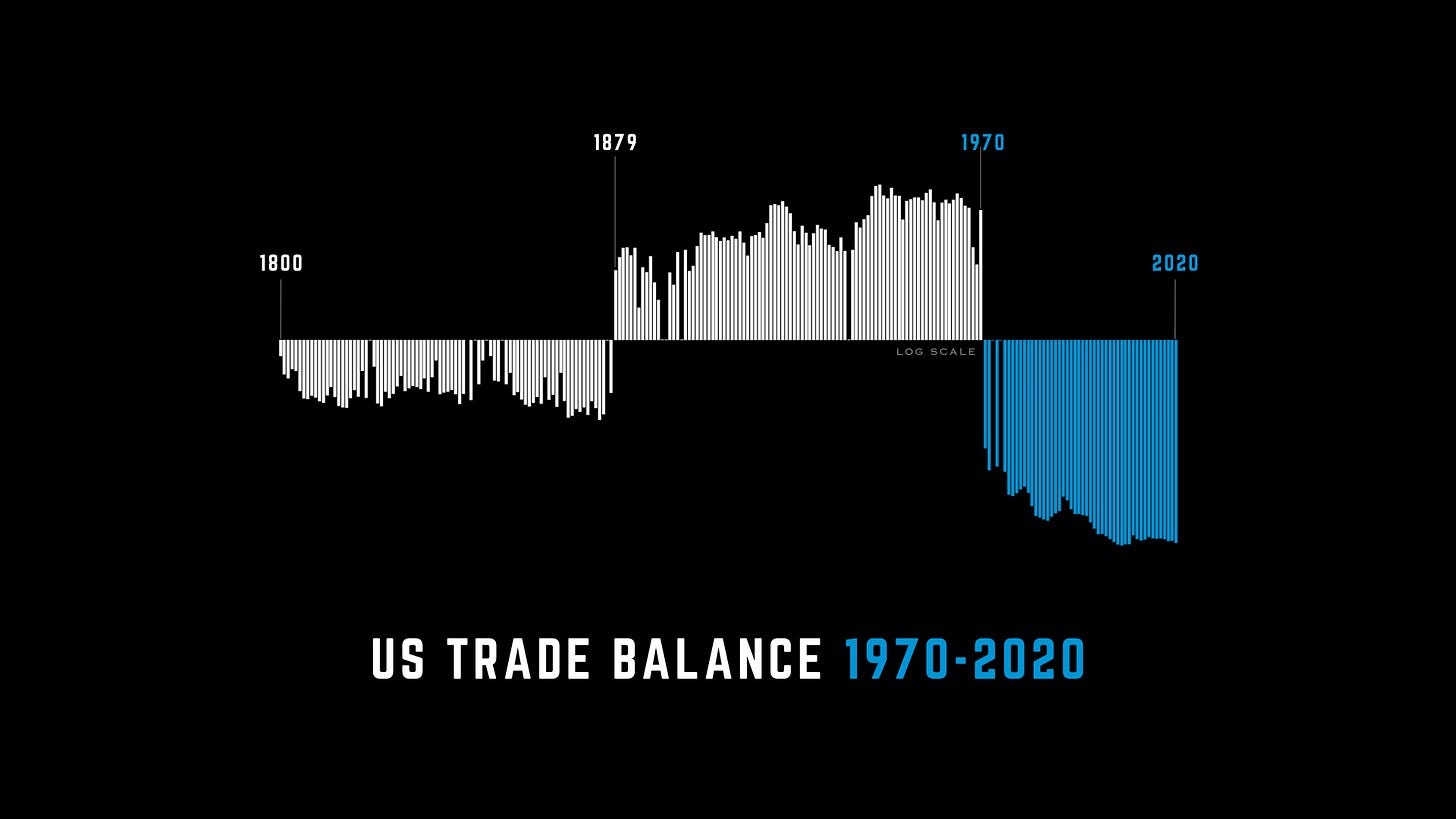

The tariffs announced by Trump last week are aimed at addressing five decades of trade and fiscal deficits that have saddled the United States government and middle class with a perilous amount of debt.

Fifty years ago, the United States was a net exporter diligently paying down debt incurred in World War II. Today, it’s a net importer that borrows to make up the difference.

The present U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is 120 percent, excluding unfunded commitments like Social Security and Medicare. The only time the ratio was even close to this high in the past, excluding unfunded commitments, was at the end of World War II, when it peaked at 113 percent.

The concern isn’t that the U.S. government will be frozen out of credit markets as would, say, an investment bank careening toward insolvency. The federal government is, and will always be, liquid and solvent given its power to tax the proceeds of the world’s largest economy.

The concern is rather that if the United States continues in the present direction, austerity will be forced upon it by rising borrowing costs in the credit markets. It comes down to arithmetic. The United States pays about $1 trillion a year in interest expense and over the next year will have to repay or roll forward more than $9 trillion of debt, the cost of which needn’t increase much to become unmanageable.

“The level of debt our country faces is unprecedented in all of history. If we don’t effectively deal with it — and soon — our system will experience a financial heart attack.”

Ray Dalio

April 4, 2025

The story of how we got here starts in 1971, when President Nixon directed the Treasury Department to stop converting currency into gold, effectively ending the gold standard.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Maxfield on Banks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.